In the News

Rising bubbles?

2nd May 2017

Where might the next asset bubble come from? With A level specifications looking for students to understand that speculation and market bubbles are an example of market failure, here are three concerns that might be highlighted:

First suggestion is that UK local councils are helping to fund a property bubbleUK local councils are helping to fund a property bubble by investing in property development. They can do this because they are able to borrow more cheaply than other speculators in the 'buy to let' market from the Public Works Loan Board, an arm of the Treasury that has been helping finance capital spending by local government since 1793. Its interest rates are linked to those in the gilt-edged market which have been at exceptionally low levels since the financial crisis of 2007-08. As a result, money borrowed at 2.5 per cent or so is typically going into property yielding 6-8 per cent or more. Read more here.

Secondly, in the housing market, is the issue that the Bank of Mum and Dad has now become the UK's ninth biggest property lender, helping to fuel a 7.3% rise in house prices last year. Housing affordability, the ratio of mean house prices to mean annual earnings, was about 3.5:1 in 1997, and is now about 7.8:1. This means that saving for the deposit needed to buy a house is way beyone the average 20- or 30-something, unless they have someone to help bridge that gap. Parents who can either release equity from their own houses, who have pension funds available for investment or other sources of capital - and who are perhaps desperate to get 'boomerang' offspring onto the property ladder - are funding 26% of all UK property transactions, and up to 62% of transactions by those under the age of 35. Is this a market failure? It certainly shifts the demand curve for housing well to the right, and it certainly favours those who have parents who can afford to help, and excludes those who haven't.

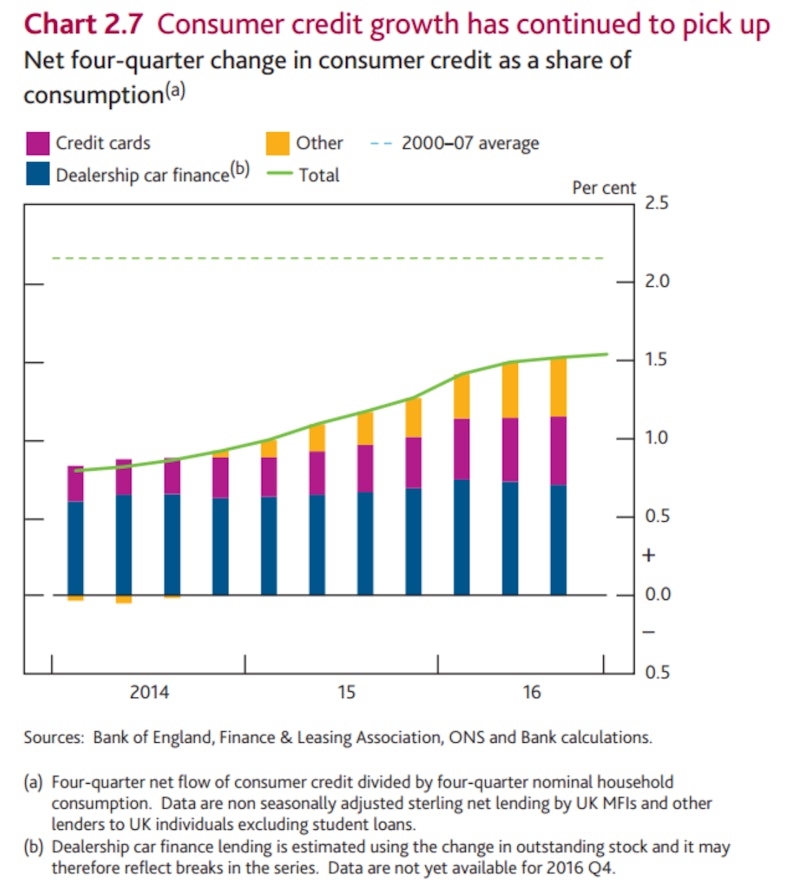

Thirdly, credit card balances. Simon Jack of the BBC tweeted last week that Virgin Money credit card balances had jumped by 8% in the first quarter of the year - and received responses that this was not surprising when they are offering 0% interest for the first 12 months for new card holders. There are now record levels of British credit card debt that surpassed £67bn this year. The Bank of England highlighted credit spending as the likely means of continuing strong consumer spending as the savings ratio is falling and as inflation begins to outstrip rises in real wages. The growth in credit is shown in this chart from page 12 of the February Inflation Report:

There may be a concern about the growth of consumer credit, and this is compounded by a report in the FT suggesting that interest free credit cards are a 'ticking time bomb'. Not for the consumers, but for the banks who are assuming that the balances the consumers are building up through the interest free periods will persist to the time at which they start to incur, and pay, interest on those balances - and at that point, the banks will start to earn profit from them. This projected profit is already being written into the banks' revenues - but what if consumers are actually better at computation than the banks are expecting, and many of them pay off the debt before they start to pay interest on it? The banks will be left with holes in their accounts. Steve Pateman, chief executive of Shawbrook, a challenger bank that does not offer these cards, said that there was a “lack of logic to booking revenues on an assumed income flow but not the assumed loss”.

Is the weakness at computation switching here from consumers to bankers?

You might also like

How a wobbly bridge helps to explain financial instability

18th September 2016

Six Lessons from the Asian Financial Crisis

11th September 2017

Game of Theories: The Great Recession

5th December 2017

Financialisation

Study Notes

The Decade The Rich Won

1st February 2022

2.5.3 Economic Booms (Edexcel A-Level Economics Teaching PowerPoint)

Teaching PowerPoints

Landlords in Limbo: Buy-to-Let Mortgage Crunch

23rd July 2024