Study Notes

Natural Resource Issues - Mineral Ores

- Level:

- AS, A-Level, IB

- Board:

- AQA, Edexcel, OCR, IB, Eduqas, WJEC

Last updated 2 Aug 2017

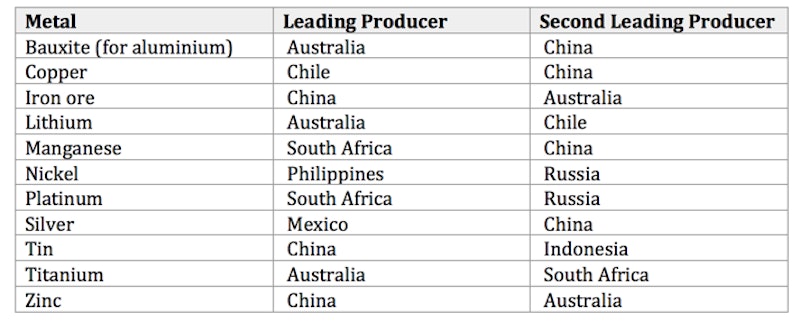

Ores are rocks that contain sufficiently high concentrations of minerals, including metals, which can be economically extracted for use in industrial processes. Like fossil fuels, there is a mismatch between global production and consumption of mineral ores.

Production of mineral ores

Mineral ores are found around the world, with patterns varying from ore to ore. Some HICs have longer histories of producing mineral ores, meaning their domestic supplies of mineral ores are heavily depleted and the reserves that are left are less economic to extract, such as copper and tin from Cornwall. There are some HICs with abundant mineral ore reserves, such as Canada and Australia, which have many decades of exploitable reserves remaining. The current sourcing trend is a shift in mineral ore production coming increasingly from LICs. Indeed, mineral ore production has been a key factor in a number of lower-income countries experiencing rapid economic growth and becoming middle-income countries, such as Bolivia and Peru in South America.

Consumption of mineral ores

Historically, industrialised HICs such as the USA, Japan and those in Europe have dominated consumption of mineral ores. As with production, patterns of consumption are now shifting to NICs (newly industrialising countries) as they use these mineral ores in their growing manufacturing sectors. The rise of China as a global manufacturing powerhouse has seen it become the world’s largest consumer of many mineral ores, including copper (for electricity cables), iron and nickel (used to make steel) and rare earth elements (REEs), which are essential to many hi-tech products.

Trade in mineral ores

Mineral ores are readily transported by bulk ore-carriers to ports close to manufacturing centres around the world. The ore is usually semi-processed to discard waste material and concentrate the mineral at the production site before being transported and is often subject to final processing once it has reached its market. Deindustrialisation in Europe and changing patterns of demand across lower-income countries has meant that the global patterns of mineral ore trade have been much more variable than those seen in fossil fuels as the market in mineral commodities is more volatile; energy demand is reasonably consistent while manufacturing cycles vary.

The economic recession following the financial crisis of 2007-08 led to lower global demand and less trade in mineral ores. Further to this, increasing recycling (of copper, steel and aluminium, for example) and the use of alternative materials (silicon optical fibre rather than copper in telecommunications) has also seen demand for mineral ores fall. The lower demand has led to falling prices for many mineral ores which has seen production cutbacks by the few mining TNCs which dominate the global trading market.

Geopolitics of mineral ores

As with any kind of trade, there are questions arising about ‘who benefits’ from the international trade of mineral ores. This is further complicated by the role of TNCs in mineral ore production. The actions of China in securing access to mineral ores have also raised questions for both the lower-income countries producing mineral ores and the countries competing with China in manufacturing which are attempting to gain access to mineral ore reserves. In order to secure sufficient mineral ores for its manufacturing needs, China is increasingly extending trade relationships with many African countries as being a continent of vast, largely untapped mineral wealth. China also possesses the financial surplus to invest in extensive mining operations and the associated infrastructure for export facilities.

As many LICs become significant producers and exporters of mineral ores, this provides a means to economic and social development. However, being resource-rich comes with a range of pitfalls that have been referred to as the ‘resource curse’. The ‘curse’ is mainly the result of the country’s economy becoming dominated and subsequently reliant on the production and export of a narrow range of natural resources, which bring a low financial return. As a result, other sectors of the economy, such as manufacturing, do not receive the investment required for growth. Mining is increasingly mechanised, so job creation is limited and that which is - often low-skilled. Furthermore, with the economy dependent on a single industry, it is susceptible to falling global prices for that resource.

In the development of mineral ore extraction, the governments of lower-income countries are likely to depend on mining TNCs for resource exploitation. TNCs provide technical expertise and the investment necessary for the large-scale infrastructure associated with the extraction, processing and movement to port facilities. As with any TNCs however, only a limited share of profits from the mineral exploitation remains in the country and many of the higher-income jobs go to foreign workers of the TNC.

Some countries have successfully avoided the effects of the resource curse and also managed to exert some control over mineral prices in order to maximise the income from their mineral deposits. Indonesia reduced exports of bauxite and nickel by requiring mining TNCs to process the raw minerals in Indonesia. Historically Indonesia has a good track-record of maximising its share of the proceeds from natural resource extraction, having pioneered new contractual arrangements with oil TNCs in the 1960s that saw the Indonesian government enjoy a greater share of oil revenues. It is now extending those legal framework strategies to the licences it negotiates with mineral ore TNCs to ensure a fairer return on profits and greater share of the higher-value processing operations.

You might also like

Evaluating stock resources

Study Notes

Measuring Reserves and Resources

Study Notes

Resource Exploration Stage

Study Notes

World’s Largest Offshore Wind Farm gets Green Light for North Sea

21st February 2015

Energy Security

Study Notes

Energy Mix

Study Notes

What is a Resource?

Study Notes