Study Notes

The Economics of (Housing) Rent Controls

- Level:

- AS, A-Level, IB

- Board:

- AQA, Edexcel, OCR, IB, Eduqas, WJEC

Last updated 15 Feb 2019

To what extent should rents paid by tenants in the private sector be left to market forces? Or is there a compelling case for some form of rent control to improve housing affordability?

Housing made available for rent from private landlords has now become the second largest form of housing tenure (after owner-occupation). There are an estimated 4.5 million households renting privately which is around 20% of all households in the UK. Well over 2 million households rent within Greater London. Significantly, the proportion of households with children living in the private rented sector has increased.

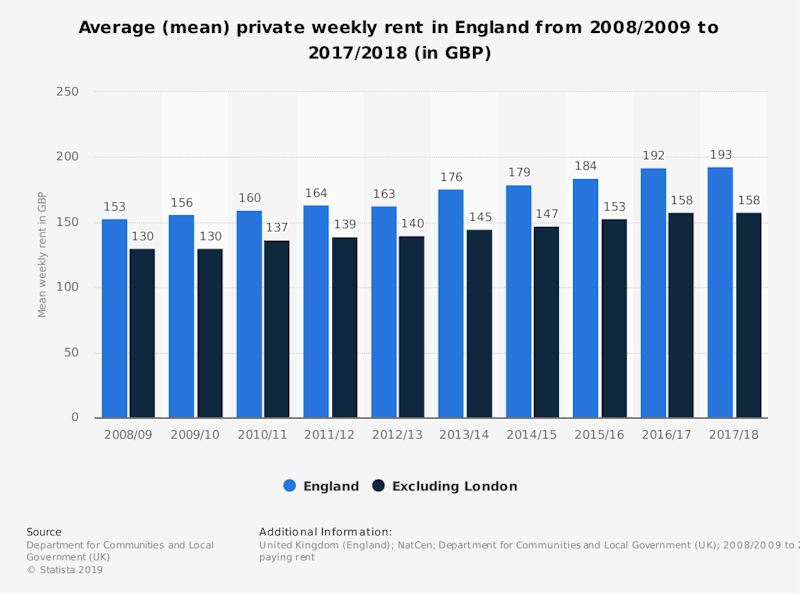

In 2017-18, the median rent for a two-bed property in London was around 50 percent of the monthly salary of a London resident working full-time. In England as a whole, the proportion was 26%.

Whilst the majority of people who rent do not find major difficulties in paying their monthly rents, the issue of rental affordability has risen up the political agenda in recent years and it is also an important economic policy concern as well.

The Mayor of London, Sadiq Khan, has made some form of rent control a central pillar of his campaign for re-election.

Rent controls would be a type of price capping or maximum price introduced into the private rental market. The detailed architecture of rent controls is important when evaluating their likely effectiveness and the arguments for and against.

For example, would the monthly rent be capped according to the council tax band in which a property is placed? Or would annual increases in rents - perhaps over a 3 to 5 year period - be limited to the annual rate of inflation (effectively an index-linking of rent levels)? In Sweden for example, rent control allows rents to change between tenancies but controls rent during a tenancy.

The pressure group Generation Rent put forward the case for introducing a monthly maximum rent amounting to half of the annual council tax band for a home.

Many supporters of rent controls actually favour a policy of rent stabilisation which is subtly different from the classic textbook approach to setting maximum prices. Rent stabilisation allows the initial rent agreed between landlord and tenant to be set by the market, but then limits maximum annual increases in rents perhaps in line with consumer prices, or the growth of average earnings in the labour market.

Others make a case for a freeze on rents so that the real level of housing rent falls each year during the freeze.

Arguments in favour of imposing rent controls

- Rent controls are needed to address the excess profits of many landlords who have been able to increase average rents as new housing supply available for rent has not kept pace with growing demand

- High private sector rents impede the geographical mobility of labour and therefore keep structural unemployment higher than it would otherwise be. Rising rents are pricing people out of housing where they live and work

- Excessive rents reduce people’s effective disposable incomes (leaving people with less to spend on food and fuel) and increase demands on the welfare benefit system.

- High rents make it much harder for younger people to save sufficient money to be able to afford a deposit on a mortgage. The average age of first time buyers in the UK has risen over the last decade giving rise to the phenomenon of Generation Rent.

Arguments against introducing rent controls

- Capping rents would result in landlords withdrawing investment. In the longer term this would lead to a diminished supply of private sector rented housing which in turn would put extra pressure on demand for social housing and more younger people would have to live at home for longer.

- Rent controls might lead to landlords cutting back on maintenance spending of the existing stock of properties and this would reduce the overall quality of rented housing and increase the risks for tenants. For example, an increased risk of damp in houses where upkeep budgets have been cut might lead to a heightened risk of asthma for families living in such properties.

- Most landlords are not part of an elite extracting rents from tenants in pursuit of big profits. Evidence from London suggests that three fifths of London’s landlords own only one extra property. A further fifth own only two. Many are elderly relying heavily on rental income as a source of income.

- Some landlords may demolish homes for rent and replace with new housing available to buy. This can accelerate a preprocess of gentrification and drive top average property prices in areas where affordability is already a major problem.

- The rapid expansion of the private rented sector over the last twenty years is evidence of the success of deregulation of rents. The chronic under-supply of rented property is not fundamentally the result of private landlords not investing enough in making more homes available for rent

Supply and demand analysis can be applied to the economics of the rental market although the theoretical diagrams shown are simplifications - for example they do not make a distinction between different types of rented property such as furnished and unfurnished, flats versus house and so on.

To be effective, rent controls would have to be set below the equilibrium free market rent. In this situation, it is likely that there would be an expansion of demand as private housing rents become relatively cheaper to the monthly cost of servicing a mortgage for home-buyers.

But holding down rents might lead some landlords to take some housing off the market since the returns (in this case the producer surplus) is reduced. The end result might be to create a disequilibrium with excess demand for properties whose rents have been capped.

The extent to which these changes take place depend in part on the price elasticity of demand for and elasticity of supply of rented housing.

Overall evaluative conclusion

The majority of economists argue that rent controls are not an effective intervention in the housing sector. Alternatives to rent controls must be considered, e.g. allowing local authorities to borrow money through the issue of bonds to increase investment in new (affordable) social housing. Rent controls imposed when the supply of housing is already chronically insufficient to meet current and future demand is unlikely to work and could well throw up some undesirable unintended consequences.

Background data:

Source: English Housing Survey (2018)

The typical deposit on a mortgage paid by a first-time buyer in 2017/18 was £44,635, down from £48,591 the year before

The average age of first-time buyers has risen from 31 to 33 over the last ten years

In 2017 tenants in the UK paid £51.6 billion in rental payments compared to £57.4 billion spent on mortgage payments.

Suggestions for wider reading

https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/rent-controls-in-london/

BBC News

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-47028342

Financial Times

https://www.ft.com/content/33442f24-23d1-11e9-b329-c7e6ceb5ffdf

The Week: Pros and Cons of Rent Control in London

https://www.theweek.co.uk/98400/the-pros-and-cons-of-rent-controls-in-london

You might also like

Rent Controls - Analysis and Evaluation points

Topic Videos

House Prices and Consumer Spending

Topic Videos

House Prices and the UK Economy (2019 Update)

Topic Videos

Does our obsession with home ownership ruin the economy?

27th January 2020

Rents collapse as tenants leave towns and cities

20th September 2020

Housing economics - turning 'generation rent' into 'generation buy'

7th February 2021